Click here to see a pdf of this webpage.

RCM at a Glance

- RCM is a budgeting system that helps management implement its corporate-centered priorities at the expense of the university’s core academic mission.

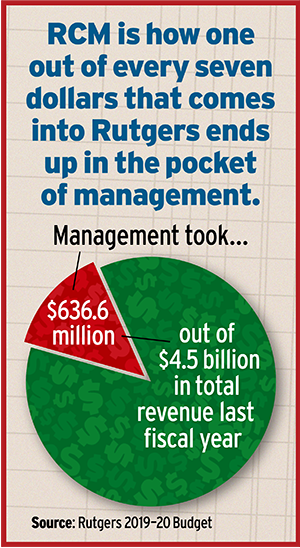

- RCM allows management to siphon off hundreds of millions of dollars each year from the parts of the university that do the teaching and research.

- RCM pressures academic and research units to impose cuts and austerity on faculty, grad workers, staff, and students in order to balance their budgets with what’s left after the administration takes its slice.

- RCM requires accountability and transparency from every part of Rutgers except the central administration, which spends huge sums however it wants to, mostly in secret.

- RCM lets management increase its own bloated ranks and fund pet projects like Rutgers Athletics.

- RCM pits departments, centers, and schools against each other, discouraging collaboration.

- RCM devalues teaching and research, pressuring departments to shift instruction to underpaid part-time faculty and grad workers.

What is RCM?

RCM stands for “Responsibility Center Management,” the name of a budgeting system that Rutgers adopted under the Barchi administration in 2014.

Under RCM, management siphons off hundreds of millions of dollars each year from the parts of the university that do the teaching and research. The central administration spends that money however it wishes, with no accountability. But academic and research units have to balance their budgets after losing a hefty share off the top.

Thus, the administration not only gets a smokescreen to hide the transfer; RCM pressures everyone else to fight over what’s left. Schools, centers, programs, and departments become responsible for imposing the cuts and austerity that are inevitable when they are forced into a financial straitjacket by RCM and have to make decisions based on what costs less, not what’s best for academics. Faculty, grad workers, staff, and students all pay the price.

Ultimately, RCM is just a budgeting tool. The deeper problem is management’s corporate-centered priorities and principles that warp every aspect of financial decision-making. In theory, RCM could be altered to work more fairly. But the greater challenge for us is to stop Rutgers from being run as a business—and refocus the university on its core mission of teaching, research, and service.

How does RCM work?

RCM requires each individual academic unit to pay for its expenses out of the revenue it generates (from tuition, grants, and other sources), minus a portion of revenue transferred to the central administration. This “cost pool transfer,” which ranges from 20 to 25 percent of academic units’ revenue, is ostensibly for “general overhead (‘taxes’) for strategic initiatives at the University and chancellor levels,” according to a University Senate committee report drafted when RCM was adopted.

Some of the transfers go to centralized expenses, like libraries and information technology, that are crucial to the mission of a public research university. But that’s not all our departments’ “taxes” pay for. Well over half of the transferred revenue stays in the central administration’s pocket, to spend on whatever “strategic initiatives” it wants.

Last year, the central administration kept $636.6 million for itself—nearly one out of every seven dollars that Rutgers took in. That’s money that academic units generated but couldn’t use for teaching and learning—to maintain an adequate teaching and support staff, to offer enough courses to keep class sizes down, to sustain initiatives critical to department missions.

At an emergency SAS meeting called in October 2020 to protest his layoff plans, Peter March, executive dean of SAS New Brunswick, acknowledged that the cost pool transfers are “effectively taxes, although we don’t like to say that.”

Maybe we need to dust off an old slogan: “No taxation without representation.”

How does RCM affect me?

Because RCM forces every part of Rutgers other than the administration into a financial bind, departments are pressured to make budget decisions based on what’s “cost-effective,” not what’s best for academics. We all feel the consequences.

The impact is particularly hard on underpaid adjunct and non–tenure-track faculty and grad workers. Because RCM guarantees a never-ending scramble to balance shrinking budgets, departments are forced into short-term fixes instead of long-term planning. Since RCM was introduced at Rutgers in 2014, the number of tenured and tenure-track faculty has stayed flat, even as student enrollment increased by more than 3,000. Instead, more non–tenure-track and part-time faculty were hired, reducing the proportion of tenured and tenure-track faculty from 35 percent to 31 percent.

Then the pandemic struck, and management began laying off Part-Time Lecturers in alarming numbers. In addition to those lives being upended, poorly paid and overworked grad workers end up with a greater share of the teaching burden—even as departments wanting to extend funding for grad students find themselves hamstrung by RCM. The workload has grown for full-time faculty, especially at a time when virtually all classes are online. And management has used the excuse of the COVID crisis to lay off or “restructure” support staff.

At the end of this chain of cause and effect are students. Smaller class sizes are critical to academic success, but the pressures of budget-balancing lead to larger classes. Learning at Rutgers has become more chaotic and challenging as faculty and grad workers are increasingly overburdened in the name of cost efficiency and the administrative staff who keep departments running face cuts. And the “financial discipline” imposed in the name of RCM has done nothing to restrain steadily rising tuition costs.

What about the money the administration siphons off? What do they do with it?

It’s not always easy to tell. Management demands transparency and accountability in how every department and center on every campus balances their budgets, but they are unaccountable and secretive about their own decisions.

One of their favored “strategic initiatives” is Rutgers Athletics. The annual administration subsidy to cover the athletics program’s losses has ranged between $25 million and $40 million for years. And this year, we learned about an unexplained $76.1 million increase in the program’s “internal debt.” Meanwhile, the rest of Rutgers is forced to make painful cuts.

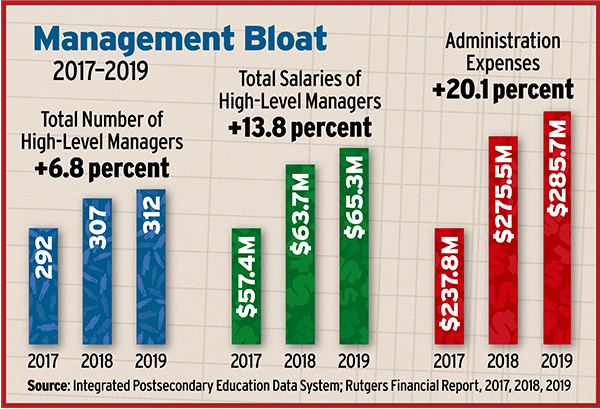

Perhaps the worst waste of all is the bloated management resulting from a central administration that never has to balance its budget like everybody else. The number and salaries of top managers in Rutgers’ central administration have increased faster than for any other category of employee. Rutgers has at least 37 senior managers and coaches earning over $350,000 yearly.

And don’t forget that the cuts inflicted under RCM budgeting, along with steadily rising tuition, produced a budget surplus at the end of every fiscal year until last year. Those surpluses got added to unrestricted reserves—the “rainy day fund” of at least $500 million that management hasn’t wanted to part with during the pandemic. RCM helps obscure the size of the reserves and what they could be used for.

Where did RCM come from?

RCM is a product of the corporatization of higher education. It was developed in the 1970s to introduce business principles into the running of colleges and universities. Faculty and students quickly learned the negative effects of unleashing competition in an educational setting, but RCM became popular with university managers, especially with the continuing decline in public investment in higher ed.

RCM is supposed to free schools, departments, and centers from arbitrary budgeting decisions by top administrators. Each academic and research unit supposedly gets assigned the money it brings in through tuition dollars, research grants, and other sources, and it can direct those funds however it thinks best to cover its costs and further its mission.

But as we’ve seen, the parts of the university that do the teaching and research lose a healthy share of the money they generate, so they start out with a budget pie that’s already partially eaten. And management’s calculation of costs and income at the department level is so obscure—and sometimes downright fictional—that the whole process remains an opaque, uncertain mess.

RCM was developed as a means for management to tighten its grip on financial decision-making by diminishing the power of those responsible for the university’s academic mission. If you doubt that, consider the words of Edward L. Whalen, author of the book that is considered the “bible” of RCM:

Of course, when responsibility center budgeting is first announced, every campus busybody feels threatened—probably appropriately under any system—and is sure that she or he must understand it to maintain “academic quality” and protect “academic freedom.” Keeping such nosy and usually noisy people under control is a dean’s responsibility.

What’s the impact on the academic mission of the university?

RCM inevitably leads toward division and disconnection. Departments and centers, schools and institutes, and whole campuses are pitted against each other in a zero-sum game to maximize revenue. Disciplines that don’t bring in big tuition and grant dollars are hurt the most by RCM, but even departments and centers with greater scope for generating income find themselves suffering from unpredictable, illogical administration decisions.

Every university president talks about the importance of collaboration across disciplines. But RCM undermines collaboration. Departments, centers, and schools have an incentive to “go it alone” so they can hang onto more of their revenue.

At Indiana University, an early convert to RCM, the College of Arts and Sciences lost 20 percent of enrollment in two years after the budget system was introduced. Why? Because other colleges changed their required courses and reduced the number of credits their students needed from Arts and Sciences—adding to their budgets at the expense of the university’s biggest school.

If RCM worked as advertised, the administration would be able to identify problems like these and adjust the allocation of costs and revenue so no part of the university suffered disproportionately. But whether that happens or not depends on the priorities of the administration. Without transparency and faculty and staff participation in financial decisions, RCM jeopardizes scholarship and research.

So what’s the solution?

RCM was introduced at Rutgers under Robert Barchi. The new president, Jonathan Holloway, has promised to review RCM to determine whether it is appropriate. Hopefully, he will see its flaws and either scrap it or radically alter it to ensure transparency and oversight. A lot could be done to make the budgeting process less chaotic, opaque, and arbitrary. Unfortunately, though, the review is being conducted by finance bureaucrats, without input from faculty who understand the academic mission of the university and the pernicious effects of RCM.

But ultimately, there isn’t a magic solution in adopting a different budget model. The real issue is changing the priorities that the administration pursues behind the smokescreen of RCM. We need to transform the whole way our university is run, recentering Rutgers on its core missions of teaching, research, and service. We want a people-centered university, with decisions about finances and resources in the hands of faculty, staff, students, and the community.